By Saul Molobi

In an extraordinary roundtable that bridged generations, geographies, and genres, five formidable voices from the worlds of publishing, media, and activism came together to explore the transformative potential of African storytelling. What began as a conversation became a declaration: African narratives must no longer be marginal – they must be central to the continent’s political, cultural, and economic rebirth. It signals a growing movement: where pages, screens, and people converge to reclaim the African narrative.

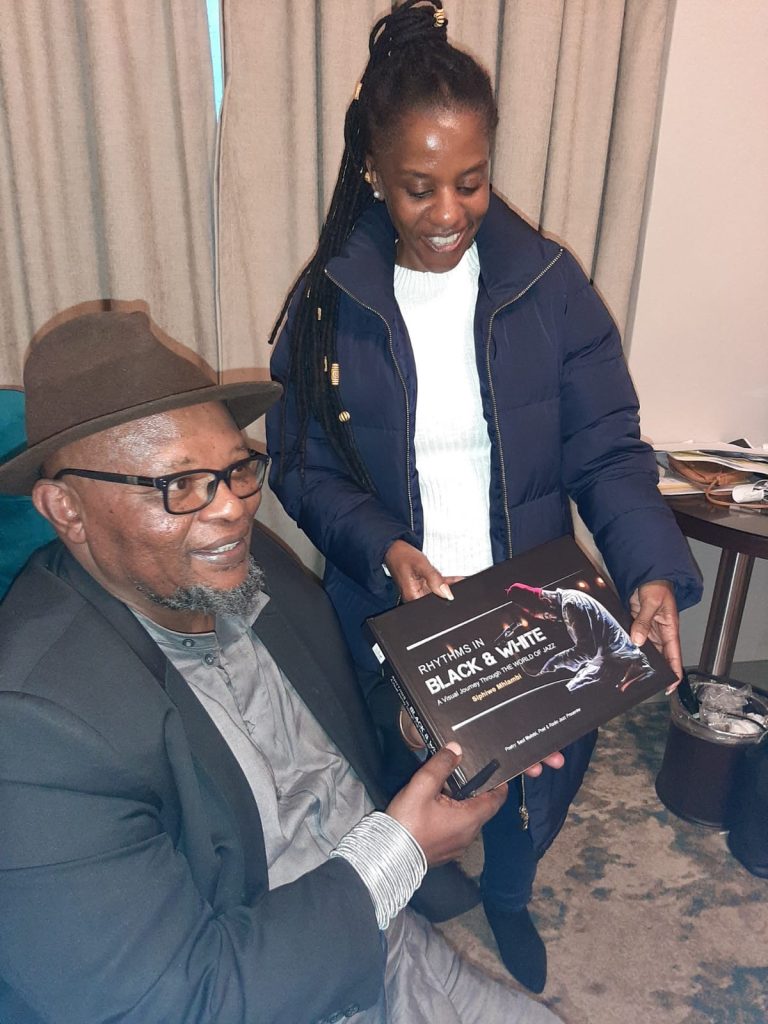

The roundtable also formed part of the celebration of Ghanaian-British publishing legend Margaret Busby’s conferral of an honorary doctorate by the University of Johannesburg on 12 June 2025. This prestigious recognition pays tribute to her decades-long contribution to literature and publishing – particularly her role in championing African and diaspora voices through groundbreaking editorial work and trailblazing advocacy. As the first Black woman publisher in the UK and editor of the acclaimed anthologies Daughters of Africa and New Daughters of Africa, Busby’s presence lent the conversation both gravitas and inspiration.

In conversation with Margaret were the South African literary activist and founder of, inter alia, the South African Literary Awards (SALA), Morakabe Raks Seakhoa; SABC’s Genre Manager: Education and Children, Jacqui Hlongwane; UK-based Pan-Africanist and reparations campaigner Luke Daniels; and myself, Saul Molobi, former diplomat and founder of Brandhill Africa.

Together, we unpacked the multiple dimensions of African storytelling – from the publishing desk to the broadcast booth, from language politics to gender justice – and how each is a battleground for identity, dignity, and sovereignty.

Publishing as Political Practice

Margaret Busby opened with a bold assertion: “Publishing is never neutral.” As the co-founder of the UK’s first Black-owned publishing house and editor of the groundbreaking “Daughters of Africa” anthologies, Busby recalled how, in the 1960s, publishing African and diasporic voices was “dangerous.” It was resistance wrapped in literature.

Morakabe Raks Seakhoa, head of wRite Associates and convenor of the South African Literary Awards (SALA), reinforced this point: “Liberation literature helped us imagine freedom before we could taste it.” Today, he believes publishing must evolve into a tool for policy advocacy, linguistic inclusion, and digital access – or risk perpetuating colonial models with African faces.

Broadcasting Africa’s Soul

For Jacqui Hlongwane, storytelling stretches far beyond the printed page. “Storytelling is also about airwaves, mobile screens, and public imagination,” she said. As SABC’s head of educational and children’s programming, she’s acutely aware of how media can shape national identity or reinforce its erasure.

Her call was urgent: “We must reflect ourselves as more than subjects of trauma – we are creators of joy, wonder, and possibility. Especially for children.” Invisibility, she warned, begins early. When children don’t see themselves represented, they grow up believing their voices don’t matter.

African Excellence: Originality With Impact

When asked what constitutes African excellence, Hlongwane was emphatic: “Authenticity. Originality. Impact.” Seakhoa added that at SALA, “we don’t just honour polished prose – we honour work that’s brave, contextual, and often produced in adversity.”

Luke Daniels took it further: “Excellence must serve the people. A campaign, a novel, a poem – if it shifts consciousness, it’s excellent.”

Daniels drew attention to how racism mutated after slavery, embedding itself in education, media, and memory. His advocacy for reparations is rooted in this understanding – justice, he argued, must be structural, not symbolic.

Pan-African Echoes: Legacy Across Oceans

One of the most moving moments came when Busby revealed that her grandfather was a delegate at the historic 1900 Pan-African Conference which was organised by Henry Sylvester Williams in London. After the conference, Williams moved to South Africa and became the first black lawyer to be admitted at the Cape bar.

Busby shared how her grandfather, George James Christian, later settled in Ghana and mentored generations of African leaders.

Luke Daniels, deeply influenced by Pan-Africanist thinkers such as C.L.R. James, George Padmore, and Walter Rodney, chipped in. He first set foot in South Africa in 1994 as an official observer of the country’s inaugural democratic elections. His experiences in Soweto and Alexandra left a lasting impression on him, sparking a series of return visits over the years. Reflecting on his connection to the continent, he declared: “Africa is home – not metaphorically, but historically.”

Women’s Voices, Global Bridges

Throughout the discussion, a consistent refrain emerged: African women writers are not just storytellers – they are stewards of cultural memory.

“We must move beyond tokenism,” Busby insisted. “There are more women writing than ever – but are they being published, reviewed, and canonised?” Her anthologies, Daughters of Africa and New Daughters of Africa, remain vital interventions that reclaim literary space for Black women globally.

I noted that patriarchy manifests not just in institutions but in which stories get silenced. Hlongwane added, “A girl who doesn’t see herself on screen as a leader is already being erased from her future.”

Language as Liberation

Language emerged as both a tool of oppression and a key to freedom. Despite Africa’s linguistic richness, its publishing industry remains dominated by colonial languages.

“You cannot decolonise literature in the languages of empire,” said Busby.

Seakhoa shared how SALA encourages submissions in all official South African languages, affirming that “excellence must be honoured wherever it lives – whether in Xitsonga, isiZulu, or Afrikaans.”

Daniels likened language to stolen memory: “They didn’t just take our land – they reprogrammed our stories. Reclaiming language is how we take them back.”

Toward a Borderless Cultural Economy

What if African stories could transcend borders as easily as Western ones?

“Imagine a Setswana children’s book animated in Accra, aired in Addis, and reviewed in Kigali,” I proposed.

Seakhoa responded with a call for infrastructure – libraries, festivals, translation networks, and cooperative publishing ventures. Hlongwane advocated for digital-first storytelling on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and WhatsApp. Daniels warned that this vision needs political will: “The market alone won’t save us. Cultural policy must.”

Redefining Awards and Archives

Awards were another point of debate. Are they tools for validation or distraction?

Busby emphasised the power of longlists: “They widen the circle. Being longlisted can launch a career.” Seakhoa shared how SALA tells each winner’s story – not just the work, but the struggle behind it.

I called for building a pan-African archive of excellence: “Not just for scholars, but for schools, libraries, and our children.”

Reparations and the Radical Imagination

Daniels closed with a poignant reminder: “We cannot heal from what we refuse to acknowledge. Reparations aren’t just financial – they’re educational, cultural, and creative.”

His vision included republishing silenced authors, restoring stolen artefacts, and funding future African thinkers. “Renaissance means rebirth,” he declared. “What was killed? And are we brave enough to imagine something new – not a mirror of the West, but a uniquely African civilisation?”

From Conversation to Commitment

The discussion ended with action. Seakhoa proposed a collaboration between SALA and Busby’s scholarship initiative to support emerging women writers. Busby welcomed it: “Let’s give them wings to fly beyond borders.”

I offered the final words: “Let’s not romanticise Africa – let’s read, write, publish, perform, and protect its voices. Not for applause, but for liberation.”

In that moment, a conversation transformed into a commitment – a living collective. A reminder that African storytelling is not waiting for permission. It is already building the world we want to live in.

Social media posts: