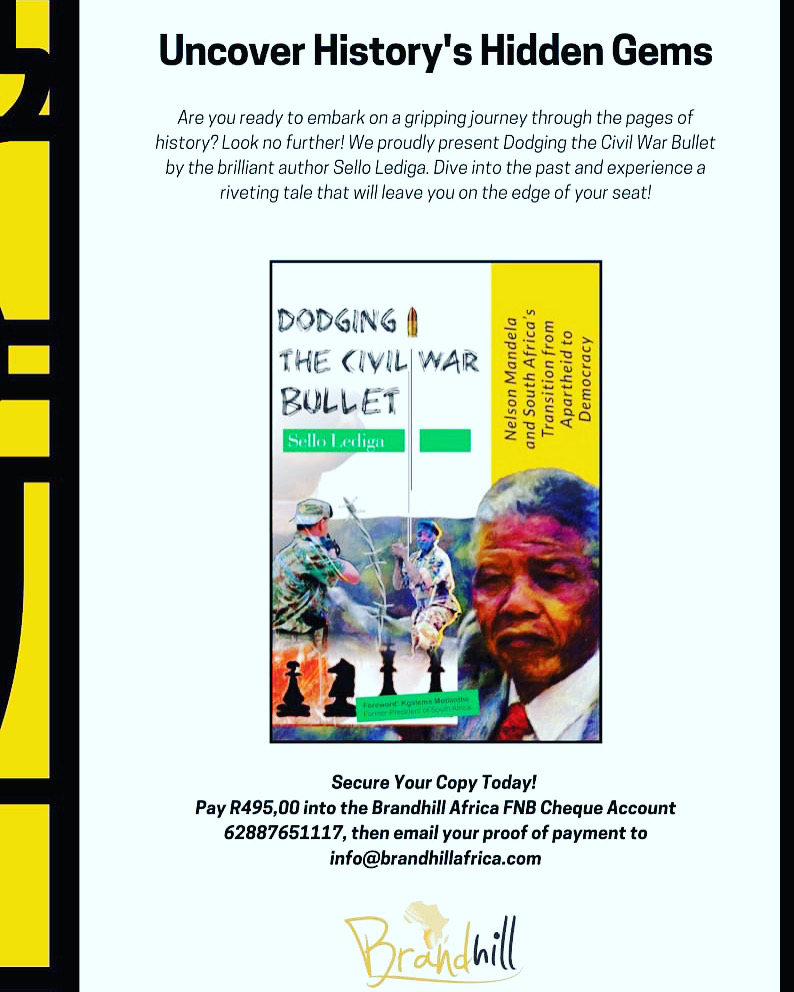

SAUL MOLOBI, Jambo Africa Online’s Publisher, goes through the “Prologue” to SELLO LEDIGA’s newly published book, “Dodging the Civil War Bullet: Nelson Mandela and South Africa’s Transition from Apartheid to Democracy” to unravel the layers of the author’s journey and the stories he has uncovered in the making of his book. His intention is to delve into the author’s experiences, motivations, and the intricate details of South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy. So going through this section of his book, he imagines himself having a question-and-answer (Q&A) session with him. This how he imagines their conversation going:

As a student of history, you felt a profound obligation to document the captivating tale of South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy. Can you share the moment when you decided to embark on this journey and capture the personalities, both prominent and lesser known, who played pivotal roles in this historic transformation?

Indeed, I am a student of history and it is on this account that the obligation to put out this work weighed heavily on me. Similar accounts of the “South African Miracle” had been narrated before; however, I still undertook to contextualise and tell this story, from an academic perspective and for the sake of first account witness recording of history, capturing South Africa’s amazing transition from an apartheid project to an internationally hailed democracy – and the personalities behind it, both the well-known and the lesser known.

The political interplay between ANC-Afrikaner dialogue groups, spearheaded by figures like Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Thabo Mbeki, Neil Barnard, PW Botha and FW De Klerk forms a compelling backdrop to this narrative. Could you elaborate on your exploration of this intricate web of relationships and the unseen forces that shaped South Africa’s destiny?

It proved to be an intriguing political interplay between ANC-Afrikaner dialogue groups that set South Africa free – it was star-studded, casting in the main the Afrikaner who can be regarded as the star of it all, erstwhile apartheid spy Neil Barnard who with the helping the background of leading Afrikaner academics and business people on the one side set the ball rolling, PW Botha and later FW de Klerk pulling the strings from behind the scenes, unseen.

The Afrikaners saw the need to engage with the ANC on the opposite end, otherwise the deluge. They were to summon courage and come face-to-face mainly with the likes of Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki among others and like PW Botha and FW de Klerk after him, Oliver Tambo played his role in the background, also unseen but his hand so obvious and so vital. It was a cauldron of nerves and strong emotions, often threatened by derailments, but the men were resolute, stood their ground.

Your journey from an incomplete Master of Art’s dissertation to a published book is quite unconventional. May you please share with us the intricacies of this journey?

This book evolved out of my incomplete Master’s dissertation. One sunny morning in 2017, I drove from Polokwane to the University of South Africa (UNISA) in Pretoria to seek admission into a Master’s programme in history. My honours degree that I obtained at the University of the North was 26 years old. I nervously found my way to the Department of History at Unisa.

A cold sweat went down my spine as I approached the office of the Head of Department of History on the ninth floor of the staggering monstrosity of the building. After introducing myself and explaining the purpose of my visit, the professor shook his head exclaiming, “So the last time you studied history was actually in 1990?”

What the professor did not know was that in that period I had published two history books, Ndizani Bafana Bafana and Tenders and the Fall of Limpopo. After pointing that out to him, the professor was convinced that I should be registered for the Master’s programme. I immediately got down to work and did my best.

And so that was how your academic pursuit began? But I believe it was cut short, what really happened?

A few months after my registration, a conjuncture of circumstances of a personal nature led to my dropping out of my Master’s programme. It was a serious setback for an academic returnee. A year later, in my frustration, I decided my effort would not go to waste.

Having written two books, I took an unusual decision to convert my dissertation efforts into a book. The rest, as they say, is history. Here we are now!

You met with Dr Neil Barnard, a former apartheid spy. How did your encounter with him influence your perspective, and what challenges did you face during this cloak-and-dagger encounter?

It wasn’t easy swopping a Master’s for a book. However, I experienced a deep passion to tell the story of how South Africa made the transition from apartheid to democracy. In this journey, I had to do the unusual, one of which was to seek an appointment with Dr Neil Barnard, the top apartheid spy who had already published books and articles about this brave engagement process with the ANC.

My appointment to meet up with Barnard was particularly daunting. Politically I was brought up to believe that spies were dangerous, never to be trusted and to be avoided at all costs – and in this instance this particular one especially, one decorated with apartheid credentials. So, when Barnard invited me to meet him at some obscure small town in the Western Cape to talk about the transition, I was both excited and nervous, maybe even feeling somewhat scared.

I arrived at the appointed restaurant, and he was nowhere to be seen – I thought well, here begins the spook games. The place looked isolated, and this didn’t do much to improve my personal situation, characterised already by self-doubt and immeasurable anxiety.

Twenty minutes later, twenty minutes of a Karoo climate sweat build-up, a tall guy, looking Afrikaner to boot, startled me with a tap on my shoulder. He asked I identify myself and with that said I should follow him.

I was a nervous wreck. Minutes later, in a rather cloak-and-dagger fashion, I was face to face with Barnard. In typical Afrikaner courtesy, the Doctor extended his hand and said, “Hello Sello, welcome”, as he offered me coffee.

The meeting with Barnard proved to be one of the most politically and academically enlightening encounters of my life. I gained rare insights into the South African conflict, the most intractable in the 20th century. I left that small town a better person.

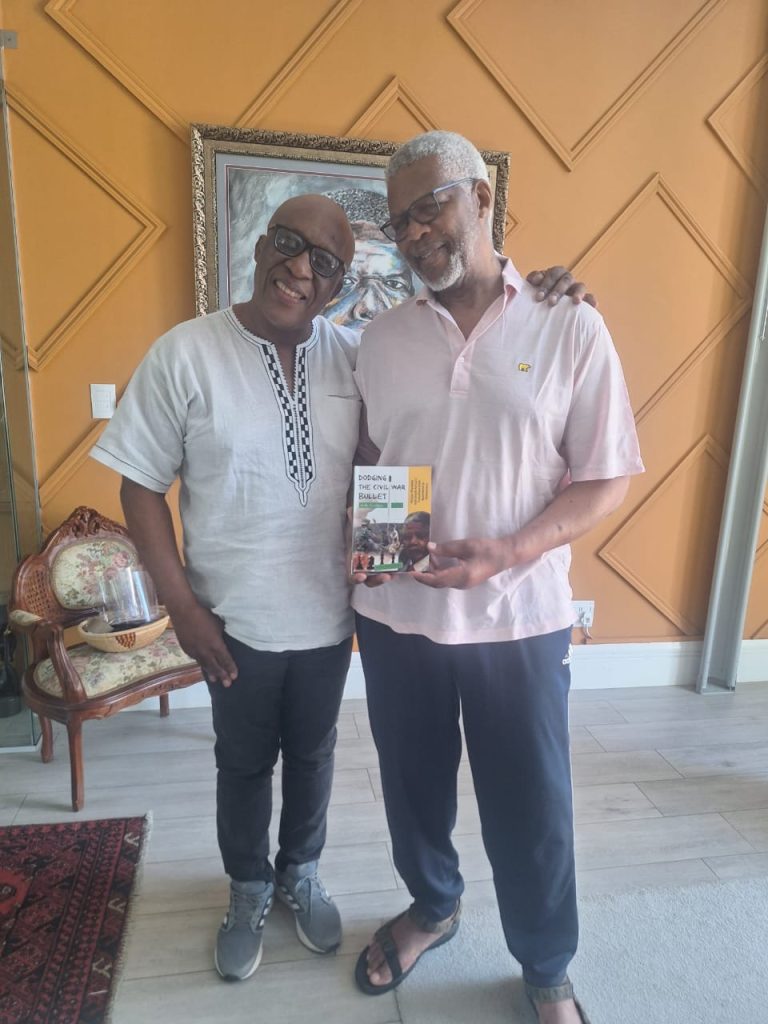

In your civil society activism, you encountered Mavuso Walter Msimang, an ANC veteran. How did Msimang’s insights contribute to your understanding of the ANC and its workings, and how did this enrich the content of your book?

In my five-year odyssey in civil society activism after I let my membership of the ANC lapse in 2016, I met a remarkable man called Mavuso Msimang.

An ANC veteran who was a member of the military high command of Umkhoto we Sizwe – military wing of the ANC – in the late 1960s. Mavuso served as the chairperson of Corruption Watch when I met him. He sought me out after reading my second book Tenders and the Fall of Limpopo.

The relationship with Mavuso continues to this day and continues to help me understand the ANC and its workings. This has enriched the content of this book. I am greatly indebted to Msimang for his experiences, patriotism and integrity.

As part of your research, did you interview other leaders from the national liberation movement?

Besides Barnard and Msimang, I interviewed some of South Africa’s political luminaries like Sydney Mufamadi, Wally Serote, Mosibudi Mangena and others. This was over and above reading scores of books, journals and articles to seek a profound understanding and context of the transition from apartheid to Democracy. My attempts to interview Thabo Mbeki, sadly did not bear fruit due to his tight diary.

Interviewing political luminaries and delving into the history of Khumalo Street, you’ve painted a vivid picture of the struggles and sacrifices during South Africa’s political wars. Could you share more about the experiences and stories that stood out to you during this exploration?

Khumalo Street in Thokoza in the East Rand, was the battle ground between the ANC-IFP political wars and too many lives were lost, not only among the adversaries but some journalists too were caught in the internecine – that’s where Ken Oosterbroek, an acclaimed white photo-journalist working for The Star newspaper in Johannesburg, got killed. Oosterbroek was shot and killed by members of South Africa’s National Peacekeeping Force (NPKF) while on an assignment. Ironically, he was killed on April 18, nine days before the April 27, 1994 elections in South Africa, the country’s first all-race elections.

And for another layer of dramatic effect in your narrative, you visited the site of violence in the East Rand?

Yes, fuelled by the curiosity of its notoriety, the Chapter would not be complete without revisiting the Khumalo Street events. My irrepressible urge to replay the violent drama that took thousands of lives between 1990 and 1994, got me to meet Ike Motloung in 2022 to inspect “The Theatre of War” that cost so much in human life.

Motloung, a former general secretary of the Katlehong Civic Association and a highly esteemed attorney today, was more than willing to drive me through the historic battlefield. I saw the monstrously huge Thokoza hostel, the rearguard of IFP gunfire, and the Katlehong township as well as other neighbouring townships who were at the receiving end. He related in detail how the so-called “black-on-black” violence that devastated the area and left thousands dead unfolded, death and destruction described by many as a low intensity civil war.

The transition from apartheid to democracy was marked by bloodshed and violence. How did the black-on-black violence in places like Khumalo Street shape the trajectory of South Africa’s history, and how did you navigate the complex narrative surrounding The Third Force?

Yes, the transition from apartheid to Democracy was indeed a bloody affair in terms of black-on black violence that will forever remain etched in the memories of those who lived through it. The scars of this bloody episode are still felt today. It was a bloodbath generally believed to have been fuelled by The Third Force, a killing machine and phenomenon set up by apartheid agents.

The decision to publish your book with Brandhill Africa and securing a foreword from former president Kgalema Motlanthe is noteworthy. Can you reflect on your encounter with Motlanthe and how his involvement added depth to your work?

My encounter with former president Motlanthe was both daunting and inspiring. Although I had seen him from a distance in the past, I had never had a close and personal contact with the struggle hero. Arguably he is the most respected political leader of our time. Courteous to a fault, Motlanthe is a humble and inspiring human being. Even in situations where he is the most important person in the room, he makes you feel more important than he is.

Such humility is rare among politicians. More surprising for a man of his age, Motlanthe appears to be in a state of health that incredibly exudes the kind of fitness that is rare among people far younger than he is. This man surely knows how to take care of himself and considering his brutal engagement schedule, I was truly humbled that he had accepted Molobi’s request to write the foreword. I will remain eternally privileged to have personally met this great son of the soil.

As a tribute to South Africa, your book stands as a testament to the individuals who steered the country away from disaster to a path of accommodation and peace. How do you perceive South Africa’s place among the community of nations today, considering its remarkable journey from the brink of civil war?

This book is a tribute to South Africa, above all. I will forever feel indebted to those few men and women across the racial divide that steered our country from the trajectory of disaster to one of accommodation and peace. Today we stand tall among the community of nations as a proud country that dodged the civil war bullet.