“Keepers of African memory must do for their languages what all others in history have done for theirs.”

— Prof Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, 2003 Steve Biko Annual Memorial Lecture, Cape Town, South Africa

Of all the encounters I’ve had with Prof Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o – both in person and through the pages of his transformative writings – his presentation at the 2003 Steve Biko Annual Lecture, titled “Consciousness and African Renaissance – South Africa in the Black Imagination”, towers in my memory like the majestic Mount Kilimanjaro.

If ever there was a masterclass on African literature in African languages – particularly with a nuanced focus on South Africa’s rich linguistic heritage and her countless mother-tongue authors – this, was it. Unrivalled.

In that lecture, Prof wa Thiong’o excavated the deep scars of colonialism – not only in South Africa but across the African continent, Asia, and the Americas. He exposed how colonial conquest stole more than land: it robbed indigenous peoples of their languages, distorted their histories, and reprogrammed their memory in the image of their oppressors.

His forensic analysis of South Africa’s liberation struggle – especially its linguistic battles – was a profound contribution to our understanding of cultural decolonisation. His insights into the preservation, promotion, and survival of African languages against the backdrop of colonial hegemony remain among the most significant intellectual legacies he bequeaths to us and to future generations.

Prof wa Thiong’o championed African literature in African languages not as an academic preference but as an essential pillar of the broader fight for political liberation and socio-economic emancipation. His advocacy earned him an enduring place in the pantheon of global freedom fighters, thinkers, and cultural warriors.

I first met Prof wa Thiong’o in the early 1990s when the now-defunct Congress of South African Writers (COSAW) hosted him on a speaking tour across South Africa. One moment has remained with me ever since: his challenge to us to translate his novel Matigari from Kikuyu directly into isiZulu and other indigenous African languages – not via colonial languages. That challenge, I believe, still stands today.

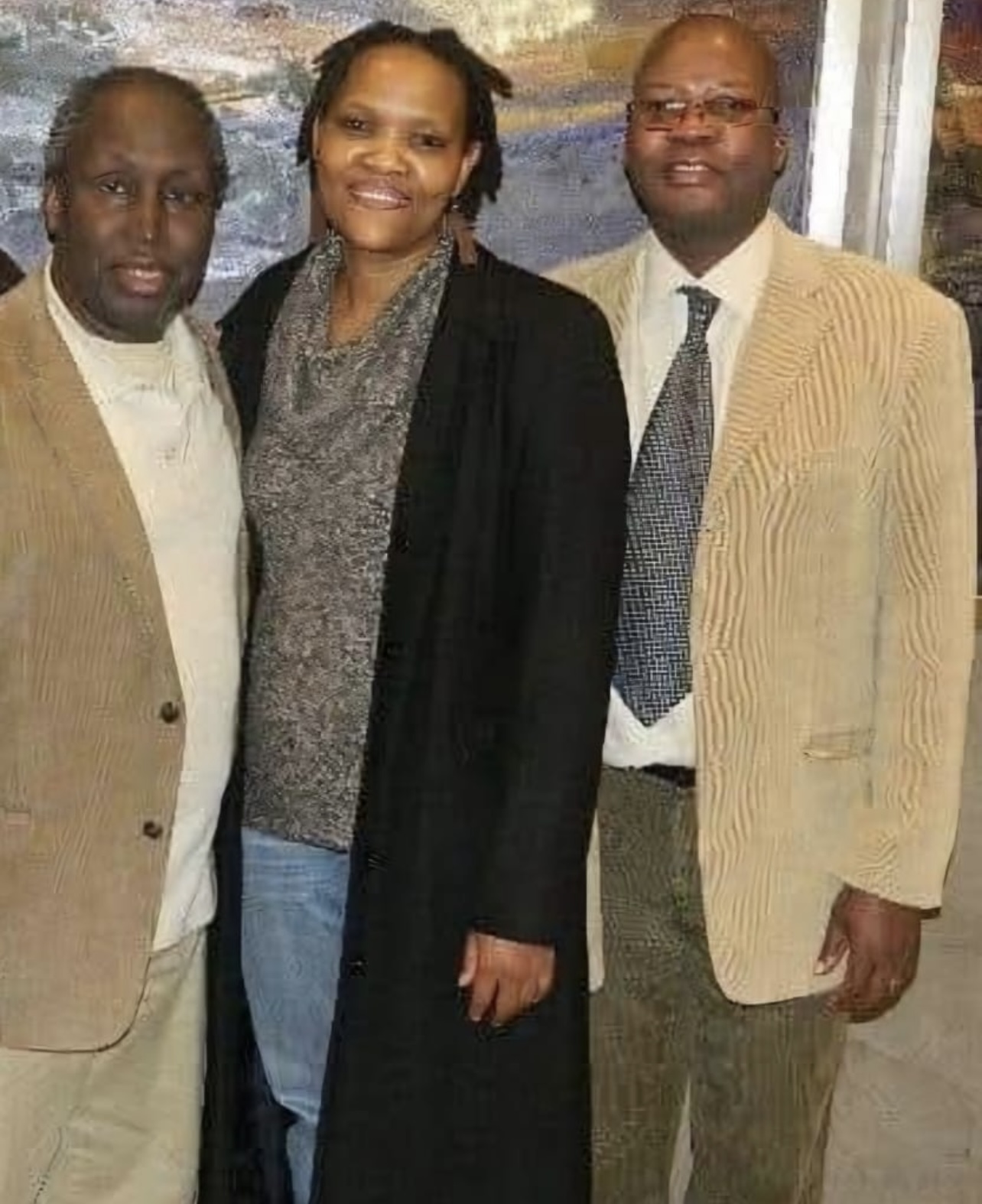

Years later, in the early to mid-2000s, as founders and organisers of what is now the 20-year-old South African Literary Awards (SALA), we reconnected with him in South Africa. We sought his guidance on our ambitions to expand SALA across the continent. He warmly congratulated us on SALA’s founding principles – particularly its inclusive recognition of all eleven official South African languages – but offered sage counsel:

“Take your time to first build and consolidate SALA within South Africa. Only when it is strong enough should you consider expanding beyond your borders.”

Prof Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has left us with an enduring roadmap to total liberation. In his own words, spoken during another South African visit in 2012:

“One of the most basic, most fundamental means of individual and communal self-realisation is language. That’s why the right to language is a human right – like all other rights enshrined in the constitution. Its exercise, in different ways both communally and individually chosen, is a democratic right.”

Rest well, Elder of African Letters.

Your revolutionary spirit lives on in all of us.

Amandla!

***

Morakabe Raks Seakhoa is the Founder and Executive Director: South African Literary Awards and Managing Director: wRite associates