This coming Wednesday, September 8, the world observes International Literacy Day. For many, it is a date on the calendar, a moment to pause and think about reading and education. But for me, it is far more personal. It summons memories of a time when the right to read was not simply about self-improvement — it was about survival, dignity, and liberation. This year I want to honour a remarkable chapter in our nation’s history: the story of Learn & Teach magazine.

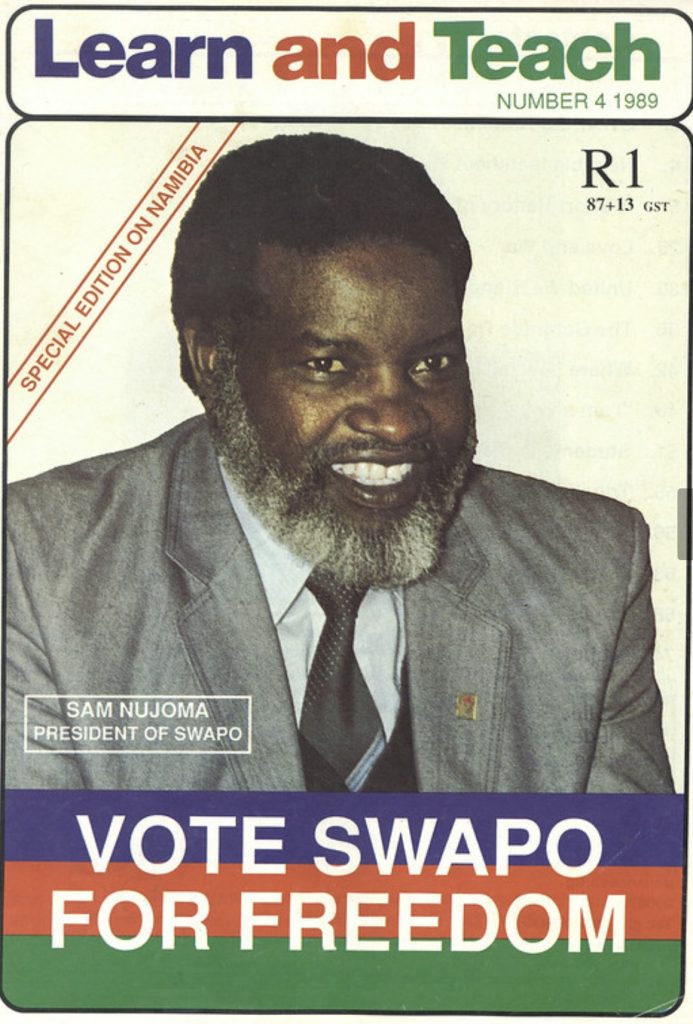

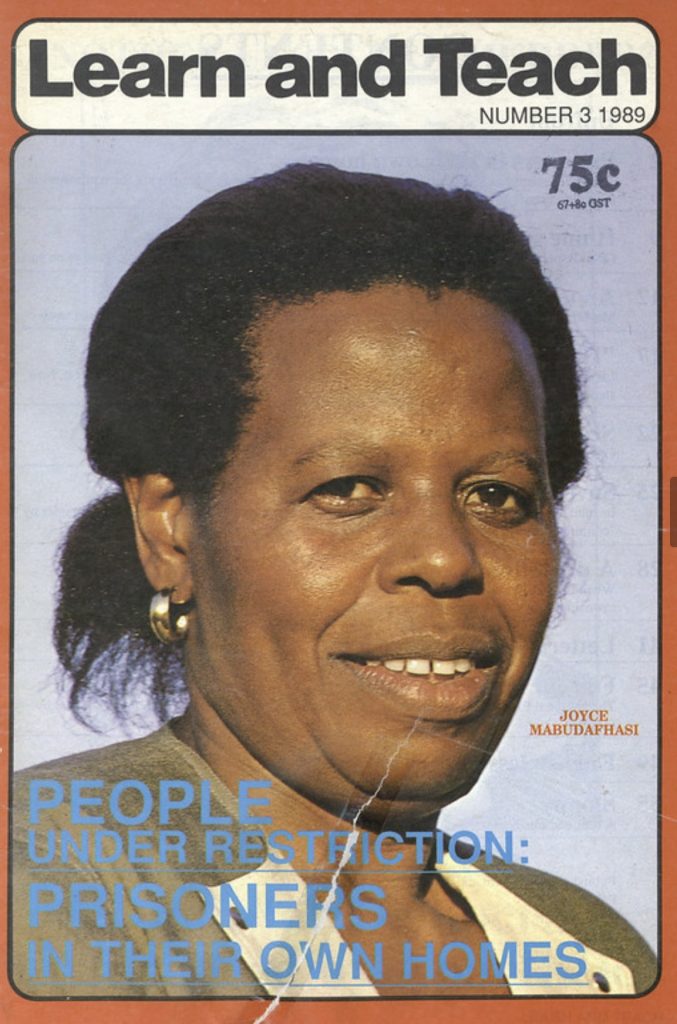

From 1981 until 1994, Learn & Teach was more than a publication. It was a bridge. A classroom for those shut out of formal education. A political education for workers and the unemployed. A trusted companion for those who wanted to understand the world around them but were told, by both poverty and apartheid, that they had no right to. Its articles were written in plain English, crafted to empower people with limited literacy. It was a revolutionary act of inclusion, a way of saying: your life, your labour, your struggles are worth explaining in your language.

But making knowledge accessible in apartheid South Africa was a dangerous act. Because Learn & Teach was part of what we called “the alternative press” — independent, community-based, and unapologetically aligned with the struggles of ordinary people. That made it a target. Entire editions were banned under State of Emergency regulations. Police raided offices and confiscated copies. At roadblocks, bundles of magazines were seized before they could reach the townships. But despite the iron grip of censorship, Learn & Teach endured. Through an underground web of comrades and informal distributors, it still found its way into homes, workplaces, and rallies.

I know this story not as an observer but as a participant. I had the honour — and the burden — of being the magazine’s last editor-in-chief. And when I say “burden,” I mean the knowledge that each sentence we published might bring consequences not only for me, but for the colleagues and comrades who gave their lives to this mission. Detention, torture, harassment, even assassination — these were not abstract fears but daily realities. Yet still, people showed up, wrote, drew, edited, translated, printed, and distributed. Their courage kept literacy alive.

I remember them.

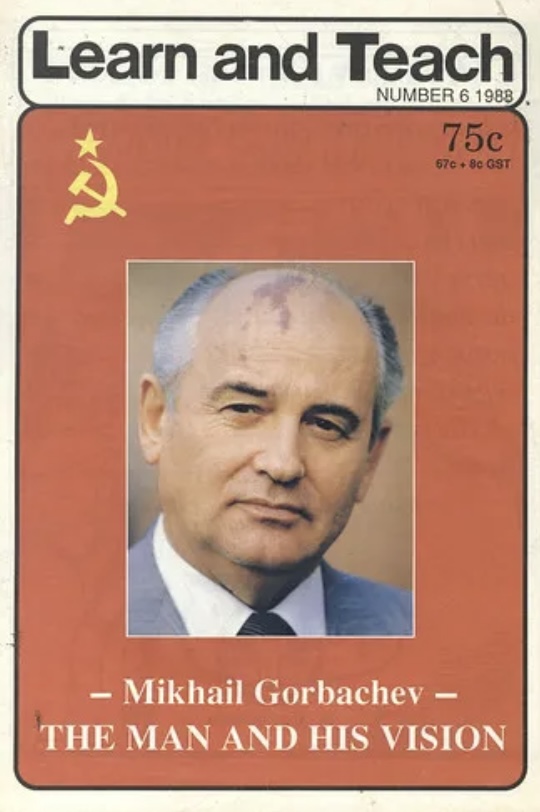

There was the legendary Marc “Sutts” Suttner, custodian of our editorial strategy from day one. Sutts was gentle in manner but unwavering in vision. He believed in clarity, accessibility, and precision. He could take complex global shifts — “Glasnost” and “Perestroika”, for example — and explain them in words that workers in a factory or commuters in a taxi could grasp. That issue, of course, was banned. But the attempt was enough: readers felt the pulse of history in their own hands. To this day, Sutts continues his life’s work of making knowledge accessible, including adapting Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom into an accessible edition. I have always said he remains South Africa’s most underutilised intellectual resource.

Then there was Mogorosi “Gori” Motshumi, a man as colourful as his cartoon creation, “Sloppy”. Sloppy was more than a doodle — he was a mirror, a commentary on everyday life under apartheid. So beloved was he that when we once published an edition without him, readers protested. They demanded his return, reminding us that even cartoons could be instruments of resistance. Today, Mogorosi lives in Bloemfontein, where he continues to tell his story — most powerfully in his autobiographical graphic novel.

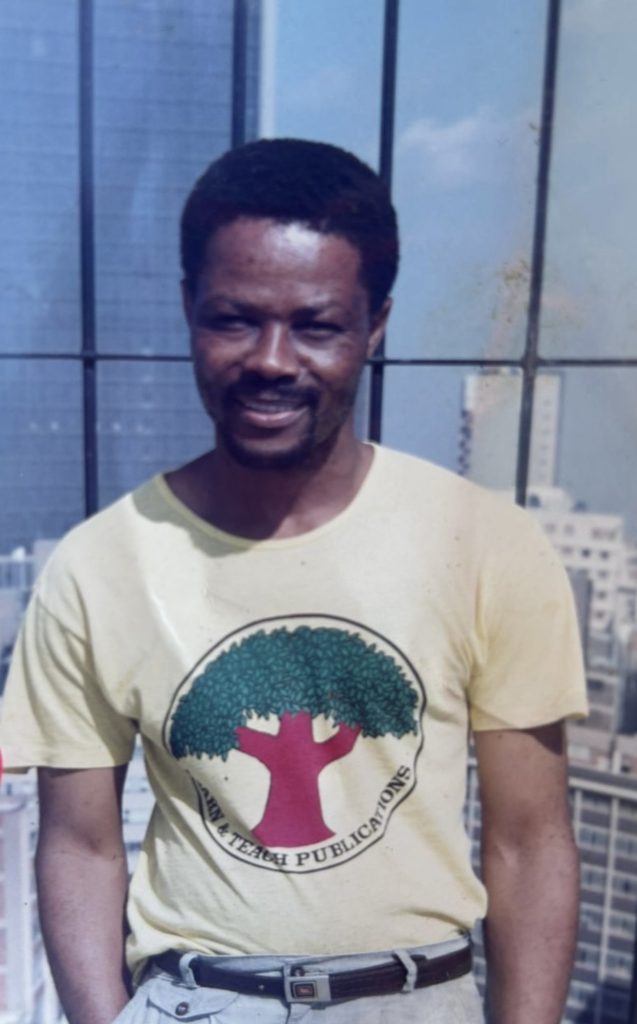

I cannot forget Phistus Mekgoe, our fearless distribution coordinator. He risked everything to make sure the magazine reached its readers. I still hear his words: “Always carry books in your car.” That was not just advice; it was survival strategy. During the turbulent 1980s, Phistus transported Learn & Teach and other titles, including works by David Philip Publishers, through roadblocks patrolled by hostile police. He supplied comrades at rallies, made sure informal sellers were stocked, and ensured that our words travelled further than apartheid’s walls. Later in life, he served as a councillor in Rustenburg, but he passed on a few years ago. His legacy remains in every reader who held one of those copies in their hands.

*** Bra Phis donning the Learn & Teach t-shirt ***

And then, there was Steve Phora — not on staff, but our number one informal distributor. On the pavements of Johannesburg’s CBD, Steve turned a small patch of concrete into a classroom. He sold Learn & Teach to taxi and train commuters, displaying them openly, even when it meant harassment and confiscation. He targeted the commuter market because he knew that words travel best when people do. To this day, Steve remains on those same pavements, selling books. He is a living legend, proof that literacy must be defended daily, not just celebrated once a year.

But the dawn of democracy brought with it an unintended silence. Alongside SPEAK, Work in Progress, Upbeat, and Saamstaan, Learn & Teach was forced to close. At the time, there was optimism that the new democratic state would support the flourishing of grassroots media. That support, however, was slow to come, and the “honeymoon” between government and the mainstream press was brief. In hindsight, it was a grave mistake to let these publications disappear. Today, we still lack a magazine that does what Learn & Teach once did: speak to the people directly, in their own voices, in their own idioms, with courage and clarity.

So these few days leading to the world celebrating International Literacy Day, I do not merely mark a date. I light a candle for those who turned literacy into an act of resistance. I remember the colleagues who risked their lives. I salute the distributors who smuggled words past police roadblocks. I honour the cartoonists who made us laugh even as we mourned. And I celebrate the readers — workers, commuters, mothers, fathers — who insisted that they, too, had the right to understand the world.

*** Hilton Schilder, jazz maestro ***

I’m glad to say this Sunday, in “Sunset Serenade” – my jazz show on 101.9 Chai FM – we will use music to tell our stories. And as Hilton Schilder’s Cape jazz idiom fills the air, I will be reminded that jazz and literacy are kindred spirits. (Click here to listen to Hilton’s latest album). Both were born in struggle, both were censored, both improvised their way past repression. A banned edition is like a muted trumpet; a confiscated copy, like a silenced drum. Yet still, the rhythm played on.

Literacy is not just the ability to read and write. It is empowerment. It is dignity. It is the right to know and the right to question. And just like jazz, it is freedom.

That is the lesson of Learn & Teach. That is the story we carry. And that is the song we play from today till September 8.

Tujenge Afrika Pamoja! Let’s Build Africa Together!

Enjoy your weekend.

Saul Molobi (FCIM)

PUBLISHER: JAMBO AFRICA ONLINE

and

Group Chief Executive Officer and Chairman

Brandhill Africa™

Tel: +27 11 759 4297

Mobile: +27 83 635 7773

Physical Address: 1st Floor, Cradock Square Offices; 169 Oxford Road; Rosebank; JOHANNESBURG; 2196.

eMail: saul.molobi@brandhillafrica.com

Website: www.brandhillafrica.com

Social Media: Twitter / Instagram / LinkedIn / Facebook / YouTube / Jambo Africa Online / WhatsApp Group / 101.9 Chai FM